By: Samantha Whitcraft, Director of Conservation & Outreach, Aggressor Adventures® & Oceans for Youth Foundation

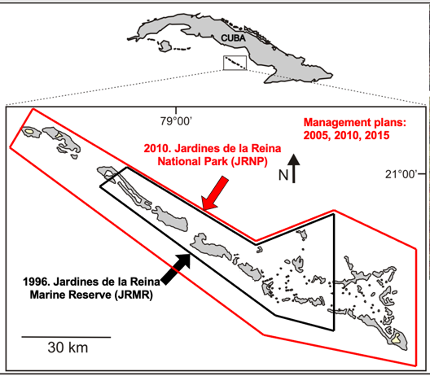

The Gardens of Queen Marine Reserve was established in 1996, and in 2010 it was expanded to become the Gardens of Queen National Park (Jardines de la Reina) making it the largest marine protected area in the Caribbean encompassing 840 square miles (2,170 km2) of interconnected habitats along the southeastern coast of Cuba. The massive park spreads across the provinces of Camagüey and Ciego de Ávila.

Within the park, this protected ecosystem is world renowned for its huge stony corals, large fishes, abundant marine life, and successful management that protects the entire coastal ecosystem and islands – from the mainland coast, out across a large bay of shallow seagrass and beyond to the intact fringing reefs. The extensive, healthy seagrass beds provide natural filtration from land-based run-off helping to keep coastal waters clean and healthy. Studies suggest that when this happens, mangroves, seagrass beds, and reefs can support more marine life. And here, they do.

The Gardens of the Queen’s designation as one of Cuba’s nine national parks is significant because such protections are enshrined in Cuba’s constitution. Terrestrially, the park’s many small islands provide protection for the critically endangered Cuban crocodile (Cocodrilus rhombifer), a rare mammal, the endemic Cuban hutia (Capromys pilorides), and vital nesting beaches for sea turtles – both green (Chelonia mydas, endangered) and hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata, critically endangered). Another endemic species, a rare Cuban palm tree can also be found on some of the islands. The shorelines of the mangrove fringed islands also provide nursery habitat for young fish such as vulnerable Goliath groupers (Epinephelus itajara).

While in the surrounding waters, much of the well-protected reef crest is dominated by large, healthy stands of critically endangered elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata). And in the reef flats, clusters of critically endangered staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) grow. Cuban scientists working in the park have documented coral spawning suggesting these reefs may serve as important sources for new coral colonies via down-current dispersal of coral larvae within the park, and perhaps even beyond to the wider Caribbean. The park’s corals are kept healthy by the cooling waters of the offshore currents and by the presence of abundant grazers such as long-spined urchins (Diadema antillarum), whose populations are declining in other areas of the Caribbean. These important grazers feed on turf algae keeping the substrate clear for the recruitment of new corals and growth of existing colonies. The abundant corals, in turn, provide ideal habitat for not only many species of reef fishes but also a readily apparent and impressive high biomass of fish.

The deeper waters of the park provide protection for spawning aggregations of several grouper species and bonefish. And with so much prey available, apex predators are also abundant including endangered Caribbean reef sharks (Carcharhinus perezi) and silky sharks (Carcharhinus falciformis). The presence of such predators is another indication of how healthy this ecosystem is.

Why is this Cuban marine park so clearly thriving? Science-based management and enforcement plans have been in place since 2005 with annual surveys by scientific staff stationed in the park aboard the M/V Oceans for Youth, a dedicated monitoring vessel. For example, in 2019, a team of local scientists surveyed 32 beaches documenting 236 hawksbill sea turtle nests and 683 green sea turtle nests. The data helped managers better understand the status of the park’s sea turtle populations and what areas to patrol more often. Importantly, nationwide Cuba has banned the capture, use, or traffic of all marine turtles.

Additionally, apart from well-regulated and limited artisanal lobster fishing, commercial fishing is not allowed anywhere within the park boundaries. However, well-managed catch-and-release sport fishing is popular with international ecotourists. The absence of extractive fishing allows fish populations to flourish. Of course, scuba diving is also popular and well-regulated. For example, all dive sites use sub-surface moorings to avoid anchor damage to the substrate and to deter unauthorized use thereby helping to regulate the rotation of dive site usage – no one site is ever used continuously to the point of any negative impacts. The number of divers admitted to the park, yearly, is also capped for the same reason. And a conservation fee charged to all visitors goes directly to support monitoring and protecting the ecosystem.

Due to the near-pristine condition of these protected, interconnected coastal habitats in the park – mangroves, seagrass, and coral reefs – recreational diving in the area provides the rare experience of witnessing the beauty of how truly healthy Caribbean marine ecosystems function.

Now, with the Oceans for Youth Foundation and Aggressor Adventures®, divers can return to explore and learn more about this jewel of the Caribbean. The returning seven-night educational program operates throughout the Park’s archipelago of islands with diving and visits across several habitats including unique lagoons, remote islands, pristine mangrove forests, extensive seagrass meadows, gorgonian dominated shallows, and deep coral reefs. Divers can expect to see large groupers and sharks on most dives along with massive schools of large and colorful reef fishes amid a background of large stands of golden, branching corals.

With the Oceans for Youth Foundation’s authorized People-to-People Group Travel Program, divers can explore the abundant waters within the park aboard the 110-foot, 20-passenger JARDINES AGGRESSOR IITM. Throughout the week, Cuban marine biologists who work in the park will host educational presentations and discussions about this protected marine environment, local conservation efforts, and the ecological importance of this magnificent and valuable ecosystem.